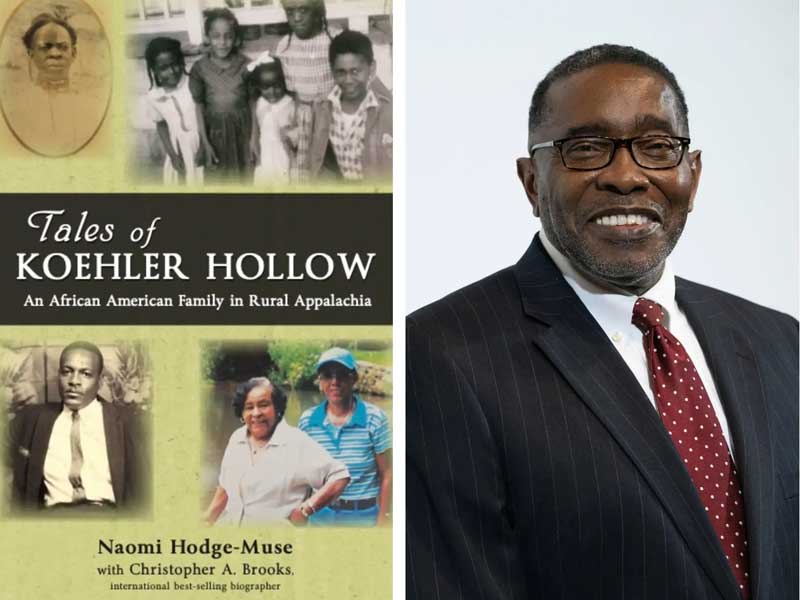

Author Christopher A. Brooks has spent his career spotlighting often overlooked stories from the African continental and Diasporan experience. His new book, “Tales of Koehler Hollow: An African American Family in Rural Appalachia,” documents the true story of a formerly enslaved Black woman and her descendants in Southwest Virginia.

The story, as told by co-author Naomi Hodge-Muse, begins with Amy Finney, who in 1890 purchased a portion of land on which she had worked while in bondage. The area, located in modern-day Henry County, came to be known as Koehler, and the Koehler Hollow homestead remains in the family today.

“This was an opportunity that I gladly embraced. That is to tell the story of a woman who had been enslaved,” said Brooks, Ph.D., a professor of anthropology in the School of World Studies in Virginia Commonwealth University’s College of Humanities and Sciences. “In many ways it is a biography as well as anthropology. We tell the story of the human experience.”

VCU News spoke with Brooks about the origins of “Koehler Hollow” and how Finney’s family story offers a lens through which to better understand the experience of Black Appalachians.

What drew you to the story of Koehler Hollow?

In 2016, [Hodge-Muse] took me to an African American cemetery in Henry County called Mountain Top Cemetery, where there were formerly enslaved Africans whose sites of interment were marked by a single brick or stone. Before that visit, I had read about that kind of thing, but I’d never actually seen it. At the time of [Finney’s] death, her son, George Washington Finney, put a marker at his mother’s interment site.

Somehow, standing there, looking at that marker, I thought, “This is an opportunity for me to tell the story of a formerly enslaved woman who, after being emancipated, worked hard to purchase the land on which she had formerly been enslaved. She bought the land, and her son cultivated it and expanded it to several acres. That land remains in the family today.” That’s what drew me to the story, and it also drew me to the family’s saga.

There’s a bigger picture, too, right?

I also wanted to call attention to the conditions under which rural African American Appalachians worked. When we think of Appalachia, we think West Virginia, we think of hillbillies – but we don’t think of the African American Appalachian experience, which is now very loud and proud. Telling that story was a motivation of mine as well.

It was very different from if you grew up in an urban area, with these rights or those rights – it was very different. I don’t want to suggest that they were broken down or hanging their heads low, but it was still a very different experience from many others who live outside of that region.

You’ve written several books about more well-known figures. How did this process compare?

When it comes to some of the better-known names that I’ve written biographies about, there was a research record and papers I could consult. But this was a very different process, in that I had to go to individuals who were around. Naomi Hodge-Muse had also done considerable research before she and I began this work.

Although Amy Finney was the matriarch, the real heroine of the “Tales of Koehler Hollow” was Naomi Hodge-Muse’s grandmother, Dollie Mariah Finney. It was Grandma Dollie, as she was known, who had a photographic memory and remembered what the formerly enslaved Amy had passed on to her. More than 65 years ago, the story was passed on to Naomi, and she remembers every single thing that her grandmother passed on to her now.

What are you hoping readers take away from this story?

I want them to understand that there is not a monolithic Black or African American experience. It is varied. It is regional. It is certainly as varied as any other person’s experience in the collective experience of this country.

For African Americans in Appalachia, and specifically the Finney family, there was a good deal of pride in who they were. There was a good deal of emphasis on family. There was what was called the Finney family grit, and that grit could work to their advantage in some instances and to their disadvantage in other instances.

Additionally, I want readers to have a new awe and appreciation for the Appalachian experience and to understand that it was varied – and that people of color, specifically African Americans, were enmeshed in it. Not only did they play a role, but are very proud to be from that region today.