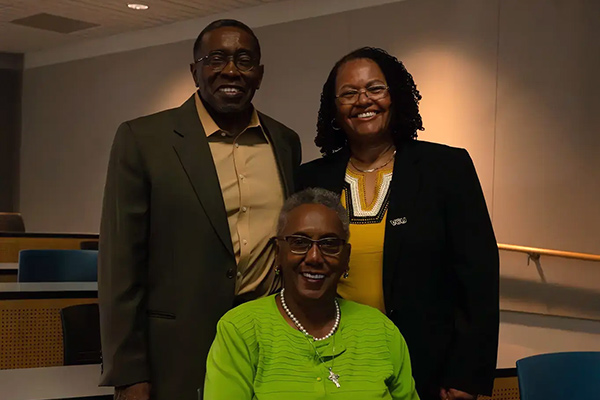

A Virginia Commonwealth University professor and his latest book’s co-author, whose family is at the heart of the story, highlighted in a recent public session the grit and richness of the Black experience in Appalachia.

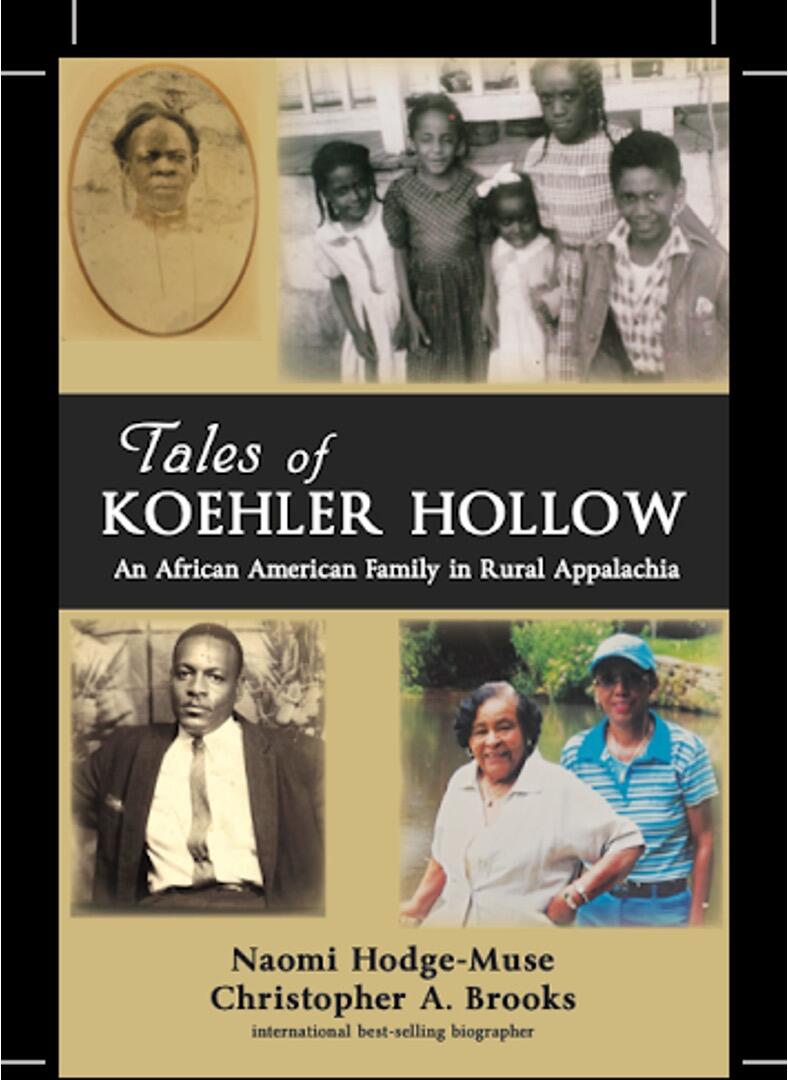

Christopher A. Brooks, Ph.D., an anthropology professor in the School of World Studies, and Naomi Hodge-Muse joined forces on “Tales of Koehler Hollow: An African American Family in Rural Virginia.” Hodge-Muse’s great, great-grandmother, Amy Finney, had purchased in 1890 some of the land, in modern-day Henry County, on which she had been enslaved. She then built her family’s homestead – a property that Hodge-Muse and other Finney descendants still call home.

Hodge-Muse, a retired executive, forged a personal connection with Brooks when they met as board members of a nonprofit, and she shared stories of the family journey.

“It was the characters in her family who really caught my attention,” Brooks said at an Oct. 30 book presentation in the Diversity in Action series, sponsored by VCU’s Division of Inclusive Excellence. “But the more and more we dealt with it, this story piqued my imagination and piqued my writer’s gut. That’s what got us started on it.”

“Tales of Koehler Hollow” – pronounced “holler,” or “holla” – presents a family story as a microcosm of the African American experience in southern Virginia from the mid-19th century to the present. Documenting the complications, joys, tragedies, and sorrows that surrounded the family, the book imparts how the characters and their identities bucked common perceptions about people from Appalachia.

Hodge-Muse said her tight-knit family personified the persistence and grit that their surroundings demanded.

“I don’t care how bad it is – you don’t sit down and have a pity party,” she said her relatives told her. “I don’t care how horrible it is. You get up and you keep moving. … Rural culture? Ain’t nobody going to give you nothing. You got to get up and you’re going to get it yourself. They ain’t going to give you nothing but a hard time and a short time to get there. So get up and get at it now.”

Brooks noted how the book project stemmed from both a fresh spark and a familiar sorrow.

“In 2016, being at the gravesite of Naomi’s great, great-grandmother, who had been enslaved, was an epiphany,” he said. “I said: Wow, here I am again, having to tell this story – to bring someone to life whose story might otherwise not have been told.”

In particular, Brooks and Hodge-Muse wanted to give voice to her grandmother, Dollie Mariah Finney – known as Grandma Dollie – who had a photographic memory and remembered what matriarch Amy had passed on to her.

“Dollie was a genius by any standard, and if Dollie were born today, she would be a judge or a university professor or something,” Brooks said. “The fact that African American women were only educated up to the seventh grade to prepare them to either work in a factory or to work as domestic servants, which is what she did – that was the tragedy of her circumstances.”

With family photos and other documents, Hodge-Muse recounted stories at the book presentation – from Finney through more recent generations – that highlighted the rhythms, challenges and even occasional capers of rural family life. She also said “Tales of Koehler Hollow” captures elements of Black Appalachian culture that might surprise some, from the presence of guns to the history of bootlegging and a love of NASCAR.

Characters in “Tales of Koehler Hollow” include larger-than-life Pokechop, who was Hodge Muse’s stepfather. There was also her uncle Ramey Finney who was trained as a barber but owned several other businesses. His sister “Wootsie,” Hodge-Muse’s aunt, was another figure who was wild by the restrictive norms facing women in her lifetime. She also recounts the experience of her younger cousin, Ronnie Lee Riley, who was gay. At the height of the HIV outbreak in the 1980s, he joined the military, contracted HIV, and died in 1986.

Hodge-Muse noted that her upbringing included pushing herself to action, notably when standing up for herself in an instance of sexual harassment during a summer factory job as a college student. She said it reflected the family hallmark of overcoming adversity and striving for achievement. Hodge-Muse returned to Martinsville after graduating from Virginia Union University, worked in a corporate role for Miller Brewing Co., and pursued an MBA – all to benefit her family financially and professionally.

“I always pushed my nieces and nephews to achieve and finish their education,” Hodge-Muse said, “and now they are executives.”