This month marks a centennial to both celebrate and contemplate at Virginia Commonwealth University – one that highlights resilience and the racism that demanded it. On a summer evening in June 1924, 10 women made history by becoming the first graduates of the St. Philip Hospital School of Nursing.

The graduates overcame intense barriers to earn their degrees and become pioneers. Early in the 20th century, when Southern law and social practice demanded segregated facilities, the Medical College of Virginia – a predecessor of VCU – established a separate school of nursing for Black women to serve at St. Philip Hospital. The hospital and school opened in the fall of 1920.

St. Philip aimed to create a parallel educational program modeled on MCV’s all-white School of Nursing, and for the first two years, the schools shared Josephine Kimerer as director. But operated independently and under the “separate but equal” fallacy, St. Philip reflected norms of the era that limited opportunities for Black women. Its students faced challenges that their MCV counterparts at MCV did not.

Inadequate equipment for training; discrimination from white patients, doctors and staff; and overcrowded student housing infested with bedbugs were among the obstacles students faced. The stark contrast in resources and respect underscored the harsh realities and systemic inequities of segregation.

Despite those challenges, there were moments of joy and triumph for the 1924 graduates. In an oral history recorded in 1984 at her Richmond home, Bertha Ree Henderson recounted her journey as a St. Philip nursing student.

“I was in training for three years. Graduated with honors. I was the first nurse who received a $10 gold piece for making the highest average under Dr. Peter Pastore,” Henderson recalled. “I enjoyed his class so much, and he was so elated over me writing my examinations the way he wanted them written that he was instrumental in seeing to it that I had received this $10 gold piece.”

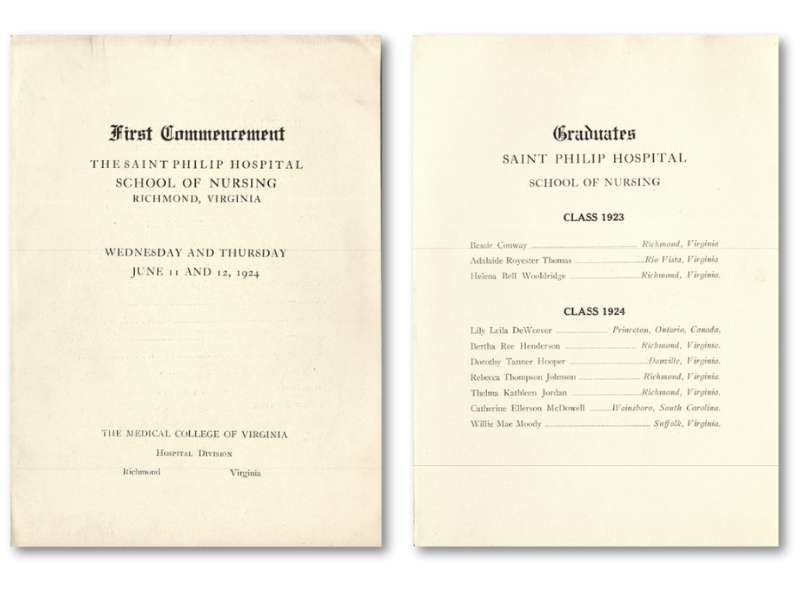

Although three women had completed the nursing program in 1923, the first commencement ceremony was not held until the following year. Graduation took place at First African Baptist Church at the corner of 14th and Broad streets (now College Street). A significant spiritual home for the Black community, the church dated to the early 1800s, when its congregation constituted the largest gathering of enslaved and formerly enslaved people in Richmond.

The program featured a host of speakers, including college and hospital leadership, whose presence underscored the significance of the event. Spiritual hymns and a sermon added to the occasion, and the evening culminated in the presentation of diplomas and pinning led by Elizabeth C. Reitz, who had become director of the St. Philip and MCV nursing schools two years earlier.

Honored that evening were the three Class of 1923 students — Bessie Conway, Adelaide Royster Thomas and Helena Bell Wooldridge. Joining them from the Class of 1924 were Henderson as well as Lily Leila DeWeaver, Dorothy Tanner Hooper, Rebecca Thompson Johnson, Thelma Kathleen Jordan, Catherine Ellerson McDowell and Willie Mae Moody.

Coming to St. Philip from near (Richmond) and far (Ontario, Canada), these pioneers went on to careers in hospital nursing, community health, private-duty nursing and nursing administration. They had endured long hours in classes such as practical nursing, hygiene and surgery taught by an all-white faculty of MCV doctors and senior nurses. They gained clinical experience on the all-Black hospital wards of St. Philip Hospital and Dooley Hospital.

And through tenacity and resolve, framed by the menace of segregation, they became some of the first trained professionals to serve communities of color – a step toward greater diversity and inclusivity within the nursing profession.

After 42 years and with integration taking hold, the St. Philip Hospital School of Nursing closed in 1962. It graduated 791 nurses, with those first 10 paving the way in challenging unjust societal norms and promoting equality in health care.