None of us at the time realized that an online post about a racist encounter in Columbia, Missouri would lead to a series of events with potential to change the demographic landscape of higher education. In September 2015, a University of Missouri (Mizzou) student subjected to racial abuse took to Facebook to decry bigotry, homophobia, and racism. What occurred in the weeks that followed raised the nation’s collective consciousness about the plight of black students enrolled at predominantly white colleges and universities. Without question, Mizzou had become the epicenter of a movement that sought to affirm the value of black lives in academia.

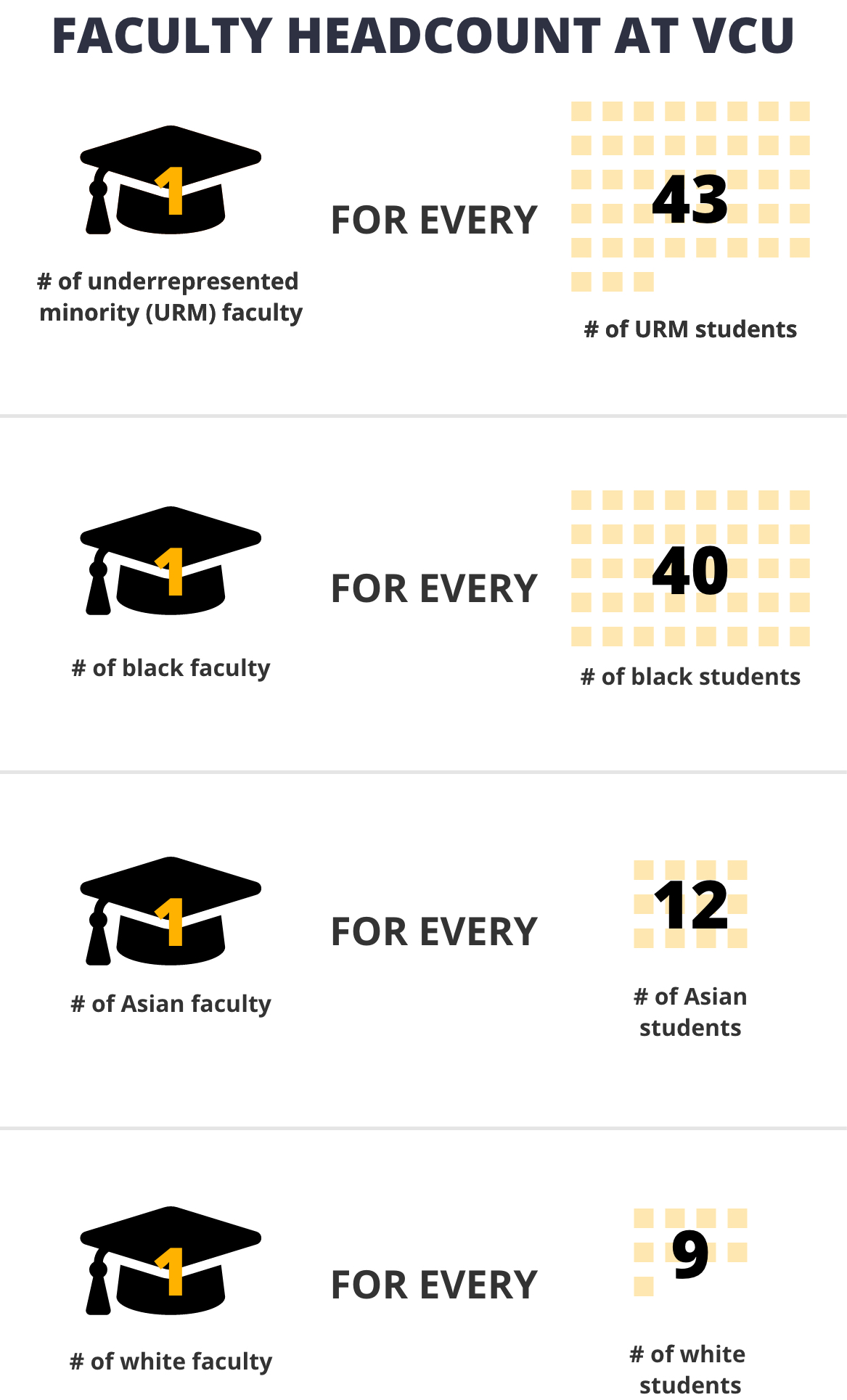

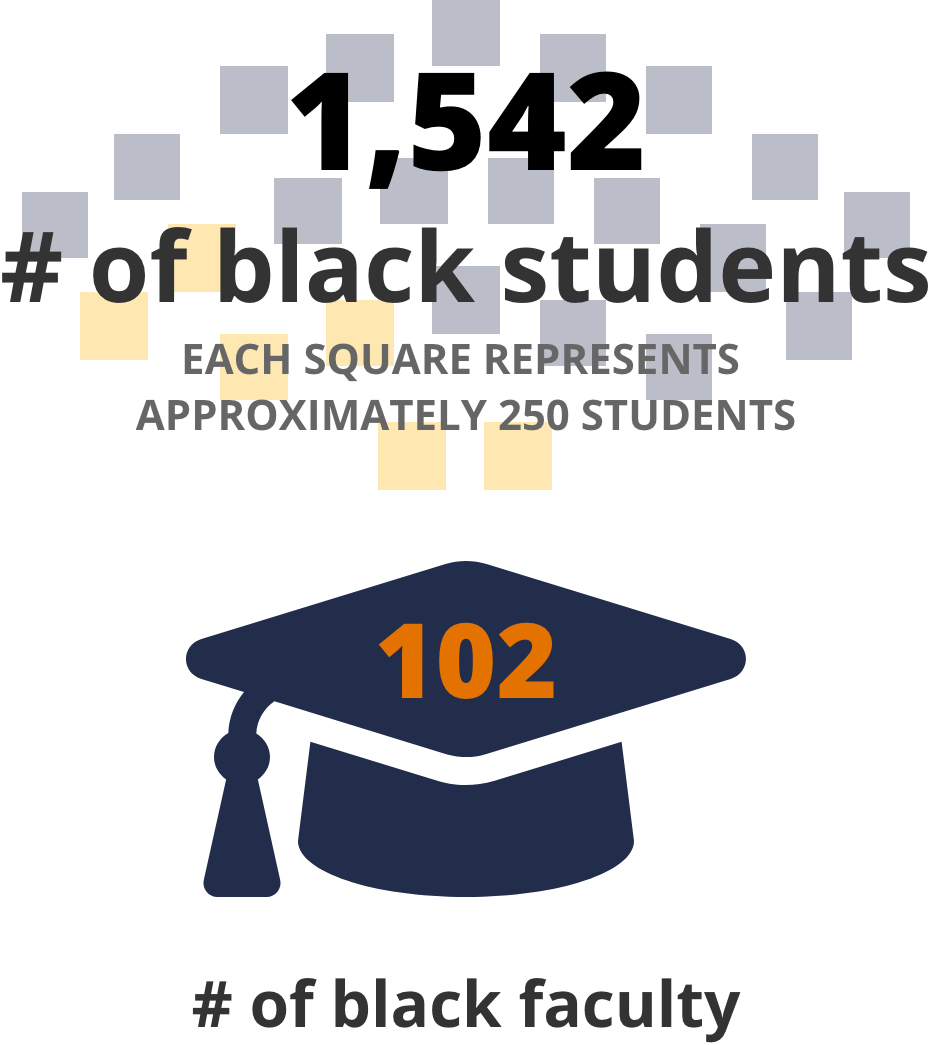

Nine hundred forty-five miles to the east, Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) students -- still reconciling a racialized incident involving a University of Virginia (UVA) student earlier that spring -- held protests and joined solidarity marches in support of Mizzou students. By November 2015, VCU students had cosigned to several lists of demands with students from dozens of other universities. The most prominent demand on each of these lists was for their respective universities to increase faculty diversity; and, at VCU, that meant increasing the percentage of black faculty from 4.7% to 10% by 2018.

We focus on the years immediately preceding VCU student demands (2012-2014) and the year of affirmation and beyond (2015-2018).

The call for increasing black faculty was related to students’ desire to have black faculty as intellectual authorities in the classroom; to engage with faculty in creative activity, research and scholarship relevant to their lived experiences; to seek guidance from faculty as mentors, role models, and support persons in both personal and professional capacities; to work with faculty to build intercultural competence among their student coevals and other faculty; and in some cases, simply to see representations of themselves in the academy.

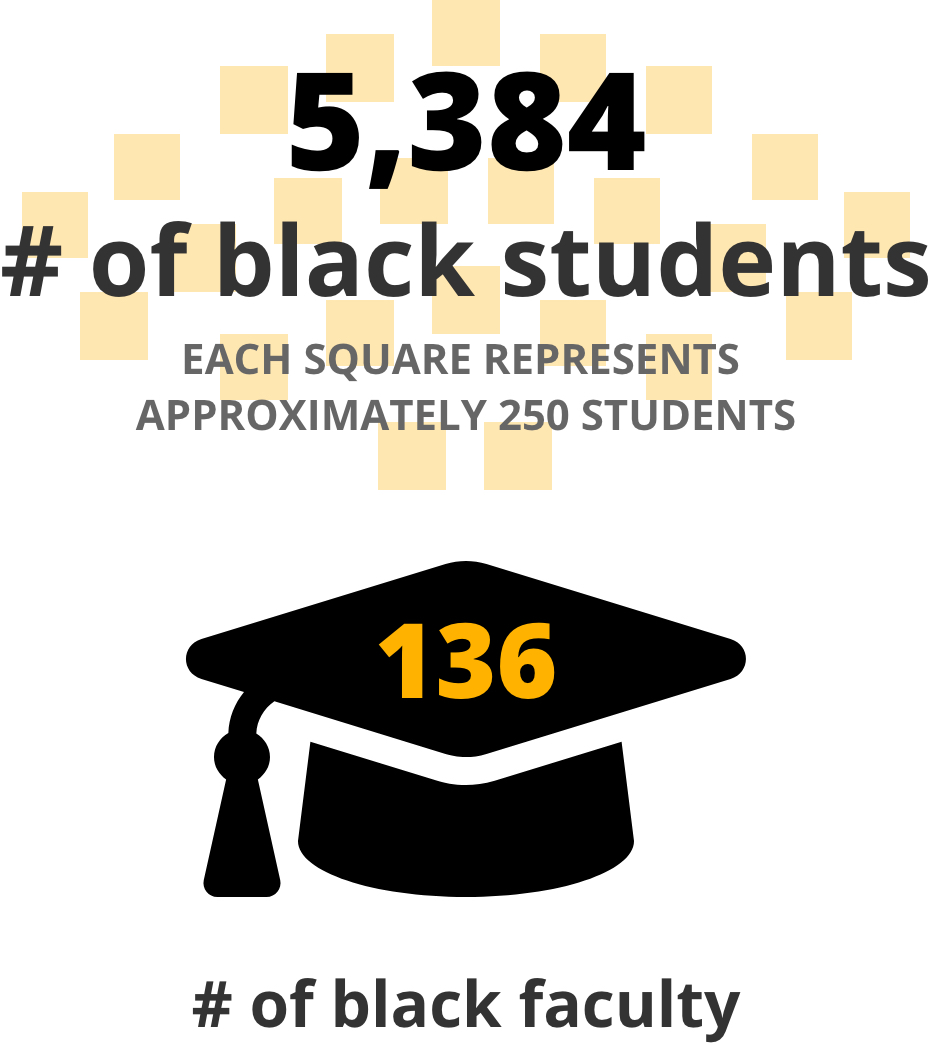

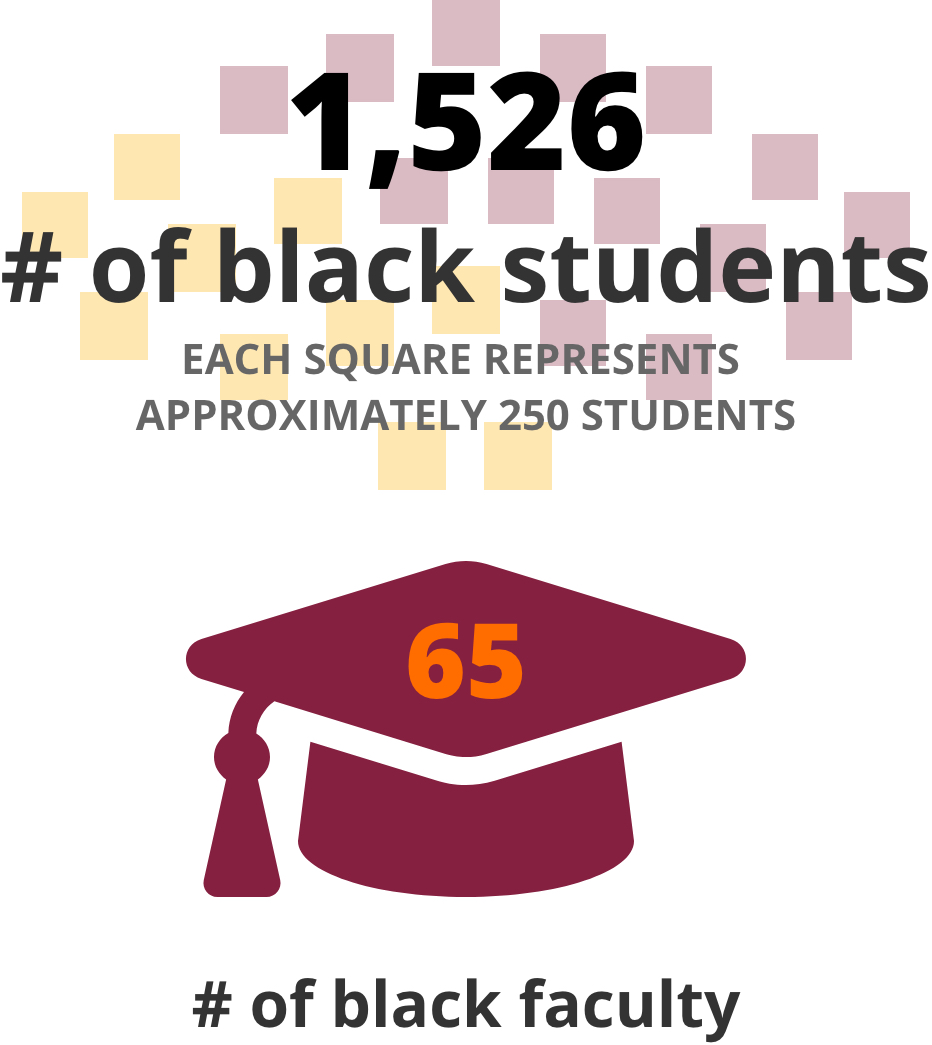

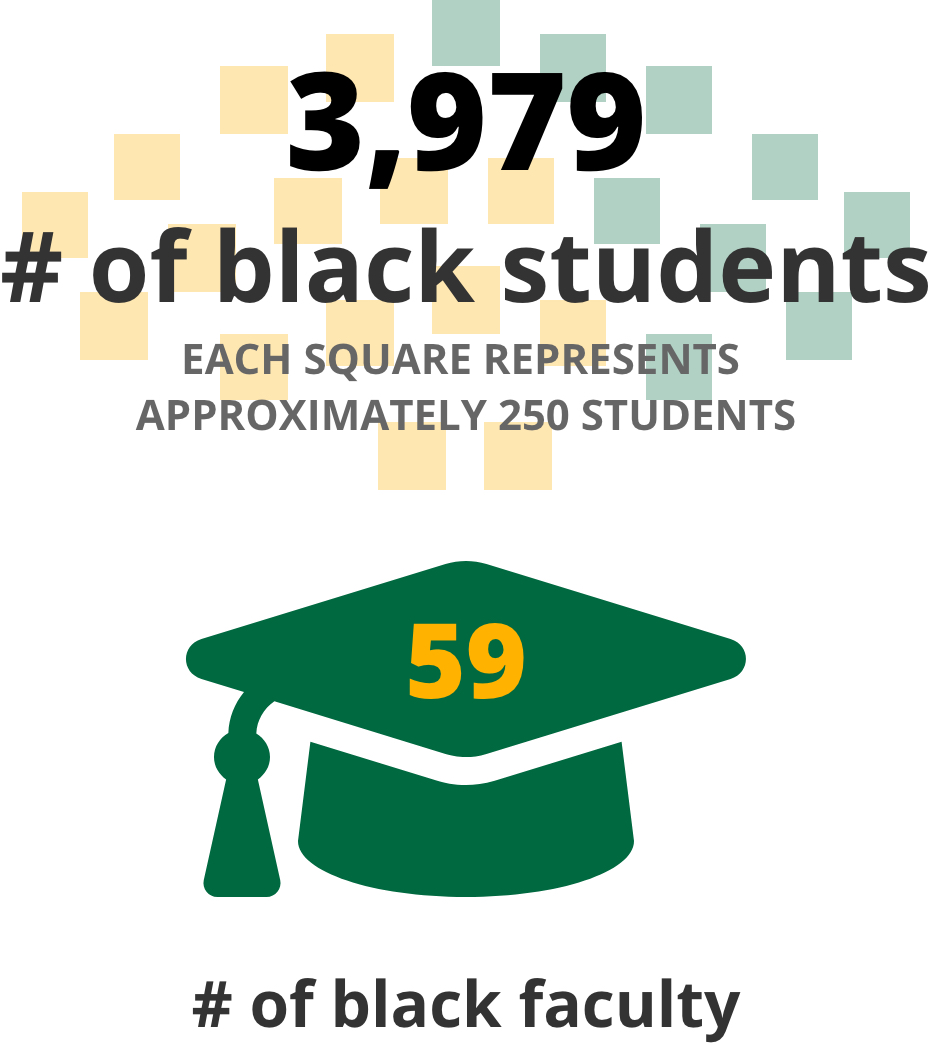

It has been a few years since that affirmation period circa Fall 2015. So, let’s take a look at how VCU responded to the call for increasing its black faculty. In this brief report, we examine VCU’s black faculty headcount, faculty-to-student proportional representation, faculty recruitment and retention, faculty turnover, and faculty success in terms of promotion and tenure. We focus on the years immediately preceding VCU student demands (2012-2014) and the year of affirmation and beyond (2015-2018). When available, we provide comparison data to other Carnegie Level 1 (R1) Doctoral Universities - Very High Research Activity institutions in the Commonwealth to better gauge VCU’s progress and relative standing.

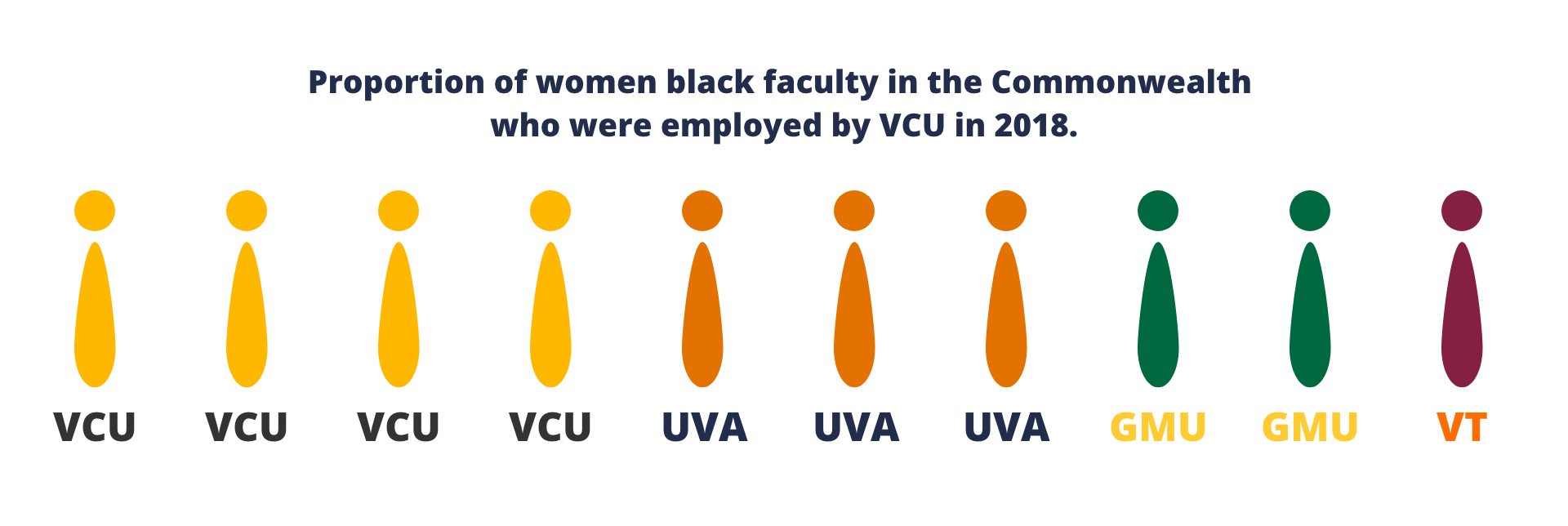

Proportion of women black faculty in the Commonwealth who were employed by VCU in 2018

Proportion of women black faculty in the Commonwealth who were employed by VCU in 2018